Khand – The Sage of Witherthorn (2020)

The tag ‘dungeon synth’ has never sat well with me. Applied retrospectively to the subgenre that essentially grew out the intros and interludes that became increasingly elaborate on black metal albums, it smacks of irony. There’s a new trend of ‘dad cool’ that gets applied to the act of obsessing over ridiculously niche subcultures. Usually ones that – to normal metrics of good taste – are horribly boring or abrasive. The term ‘dungeon synth’ seems specifically designed to appeal to these new dimensions of social status now afforded by geek culture. Like many evils of our day, I suppose we must point the finger of blame at hispterdom’s preoccupation with anti-trends as largely responsible for this.

Why labour so long on the term for this genre? Well, as with many metal subgenres and offshoots in wider metal circles, the label is not simply a benign category. It becomes a symbol, an invocation, one that all artists who move under its banner must submit to. The words themselves play an active role in determining the direction and creative possibilities within the genre it is referring to. And ipso facto it becomes self-limiting. Pioneers of the genre such Mortiis, Burzum, and Mordor were all a bit shit at keyboards, and limited by their means. But unlike black metal proper which was saddled by similar limitations but inadvertently created an awesome sound, the early works in the dungeon synth canon required a certain suspension of disbelief to enjoy. Much like the fantasy games and literature they were inspired by, one had to let go of the usual metrics of quality to immerse oneself in this archaic yet charmingly modern form of dark ambient.

If one was not to dwell in a self-satisfied irony garnered from indulgence of the obnoxiously obscure, these self-limitations were outflanked by artistic limitation on the one hand, and big budget renderings of the same in the likes of Wardruna and Heilung on the other. How does one retain dungeon synth’s low budget credentials, the unique sense of music from the past trapped in the present, without coming off as horrendously derivative? Few works have succeeded navigating these treacherous waters; Lord Wind’s ‘Ales Stenar’ and the spirit carried in all of Summoning’s work have come close.

Enter Khand. Formed in Massachusetts back in the late 1990s, they are hardly a newcomer to the genre, but have gone largely overlooked. Maybe a sign of how the subculture’s insistence that everything be released on cassette and (until recently) shirking streaming platforms are partly to blame. However, Khand released their second full length album this year, entitled ‘The Sage of Witherthorn’. Upon pressing play, we are immediately confronted with elements that set this apart from many of Khand’s contemporaries. Make no mistake, this album takes some risks as far as dungeon synth is concerned. And the key is in the second word of that term, because the synths are front and centre from the get-go here, and they make regular appearances throughout the album. Although tonally this fits very much into the synth-wave explosion of the last few years (thanks in no small part to the popularity of Stranger Things), the melodies and arpeggios they work through reference the medieval traditions that define dungeon synth’s style. Applying such a brazenly modern sheen to proudly traditional music was a risk, but it certainly pays off here.

One couldn’t talk of a Khand album without calling attention to the percussion. A drum machine is present for most of ‘The Sage of Witherthorn’. Sometimes it picks out an elaborate rhythm on the snare, reminiscent of the driving beats of much folk music. Other times a more minimal, throbbing beat is picked out on what sounds like a timpani drum, although it could just be toms washed out with reverb. But whether they are intricate or minimal, what is of particular note is the care and detail applied to crafting these drum tracks to augment the impact of the music. It’s an underrated instrument in this field and one that – if the proper time and attention is paid to it – can add new dimensions of drama and emotional expressions within a piece.

What’s remarkable is how well these distinctively modern patches work with the flutes, the harpsichords, the harps, the bells, and of course the ever-present strings. It’s all knitted together into a sweeping and diverse work that somehow manages to retain the synthetic charms that fans of the genre crave whilst expanding the sound; almost to the point where it feels like we’re listening to an orchestra. All the melodies and refrains are elegantly simple taken separately, but they are patiently layered onto one another, sometimes in counterpoint, sometimes call and response, and sometimes simply picking up the threads of the previous passage to develop the piece further. The multifaceted nature to each track comes across as the work of many musicians. Despite all this complexity however, the whole is not overwhelming, or an assault on the senses. One is simply carried along by Khand’s irrepressible ability to develop themes and narratives for extended periods.

I suppose the real joy of ‘The Sage of Witherthorn’ (and Khand’s previous LP ‘The Fires of Celestial Ardour’) is that they transcend their genre. And this, ultimately, is the hallmark of all great music. The listener forgets they are listening to synthetic, medieval influenced music composed entirely on keyboards, or music designed for video games. They are transported to a fully realised soundscape that is both technically competent and emotionally developed.

The Outsider – From Ancient Gods and Forbidden Books (2020)

What we have here is an all-encompassing symphonic metal odyssey hell bent on referencing as many styles as possible over the course of its hour plus runtime. It sits very much within the tradition birthed by Celtic Frost’s ill-fated ‘Into Pandemonium’; well meaning, occasionally interesting, but ultimately frustrating, patchy, and incredibly abrasive to some ears. ‘From Ancient Gods and Forbidden Books’ borrows in no small part from the theatrics of mid-period Therion, Septic Flesh, and Rotting Christ at their most gothic. The result is a work that – in metal terms – suppresses its more sophisticated impulses for the sake of stylised power metal and poppy industrial tendencies. This is compensated for by an abundance of orchestration, keyboards, and theatrical vocalisations to sit alongside the guttural death metal growls. When The Outsider do stray off the beaten track as far as metal and rock influences go, they lean into the realms of jazz and Latino traditions to inform their rhythms and melodic progressions.

I mentioned earlier that working metal through this melting pot of styles too forcefully can be abrasive. I don’t mean this is in the usual sense of the word. The abrasion stems from saturation. It’s the musical equivalent of a film that’s overly reliant on special effects, to the point where one succumbs to sensory overload. Emotions, moods, timbre, all jump from one extreme to the other, allowing the listening little time to keep up, so they switch off their mind in self defence.

The real substance of the metal passages is made up of halfway decent death metal riffs, poppy industrial metal, power metal, and some heavy nods to Septic Flesh. But these elements are offset by an unfocused and confusing array of disparate influences that the artist ultimately fails to master into a cohesive work; even if we give a free pass to the poppier sensibilities scattered throughout.

It’s as if the true character of this music is being constantly suppressed by an undignified circus of directionless self-indulgence. When they do appear, the genuinely engaging riffs are buried in a wash of symphonics that are not only way too high in the mix, but are often out of place. The longer, extended jams come across as a showcase for various instruments, techniques, and styles, but ultimately devolve into tedium, for the simple reason that everything occurs to the detriment of something else. Even if one could say individual elements are intriguing, enjoyable both artistically and intellectually, they are always working against the rest of the music that runs parallel.

As mentioned, the album is over an hour long. The mixing of the guitars and drums is fairly standard for proggy death metal, with enough space in the mid-range left for synths to fill out the sound, but more often than not they devolve into poppy industrial metal. Much like ‘Into Pandemonium’, it feels like risks were taken for the sake of it. Heavily orchestrated and melodramatic metal – when it succeeds – is a delicate yet rewarding artform, not least because balancing all the elements into a unified work is an artform in itself.

Things sadly don’t improve when the guest musicians show up. Kelly Shaefer makes an appearance on ‘The Headless Horror’. No disrespect to the guy, but he lost his voice many years ago, and he is placed so high in the mix that it overpowers everything, exposing the present weakness of his vocal cords. We are then treated to Jørgen Munkeby of Shining on the track ‘Suicide is Progress’, a meandering jazz piece with accompanying spoken word that – once it gains momentum – breaks into one of best riffs of the album, only to be cut criminally short by Munkeby’s obnoxious approach to the saxophone. Anyone who has encountered Shining’s ‘Blackjazz’ will be aware of the kind of directionless onanism this musician is prone to.

And from their it continues. Genuinely well-crafted death or black metal riffs held back by avant-garde leanings. Jazz held back by cheesy industrial metal. Symphonics held back by lack of purpose. And some genuinely beautiful moments (see the track ‘Beautiful’…no shit). The word is frustrating. Because a decent symphonic metal album sits underneath all these elements that are wedged in for no other reason than to be there. Diversity, variation, broadening the horizons, all are not ends-in-themselves. Mastering a vast musical breadth is not a virtue unless they can be put in service of an album that means something, beyond a showcase of music theory.

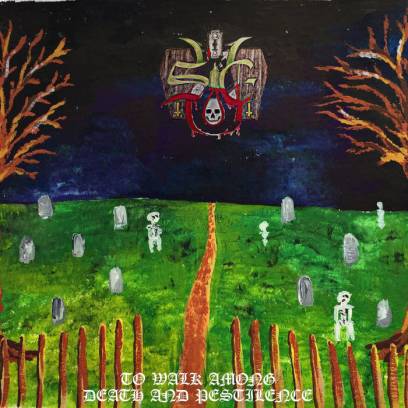

Sykelig Englen – To Walk Among Death and Pestilence (2019)

Sykelig Englen’s third LP ‘To Walk Amongst Death and Pestilence’ released last year is a rock album in disguise. I say disguise, more like a cheap pair of shades. I suppose we could hold the post 2000 trajectory of Darkthrone partially responsible for some of this. But the raw, lo-fi traditions within black metal have often made use of galloping rhythms, heavily cadenced riffs more fitting of eight bar blues, and an undeniable boogie at different points. But this can sometimes translate into a more trancey, dreamlike sequence, augmented by heavy repetition, that diminishes the domesticated foundations of the music (Drudkh for instance).

But on ‘To Walk Among Death and Pestilence’, despite the necro aesthetics and substandard black metal vocals, the rock sensibilities are front and centre. The riffs are basic and easy to follow, working through the most rudimentary tricks to vary the impact and emphasis in places. The solos belong on a demo tape, coming across as place-holders for something more developed that never actually emerged. The tempo settles for the most part on an ‘Immigrant Song’ style gallop, with little variation on the basic rhythmic framework of this track, regardless of the apparent mood the rest of the music is attempting to convey. Vocals, as mentioned, are run of the mill grim black metal, but don’t seem to correspond to any logical pattern or purpose, existing solely to fill the gaps between the next solo, or the next breakdown, because the riffs that make up the centre pieces to most of these tracks are flat and basic, devoid of any character; a framework yet to be fleshed out.

Applying rock sensibilities to black metal is nothing new. For all the obnoxious drivel black ‘n’ roll artists have pushed out over the years at least it leaves an impact, a feeling, even if that feeling is one of revulsion. But on ‘To Walk Among Death and Pestilence’ even that sign of life has been sucked out the music. What’s so offensive about the release is not that Sykelig Englen dared to tarnish black metal with the banalities of rock. Rather, it’s the fact that the finished product is so inoffensive, lacklustre, drab. Occasional melodies stick out, some unexpected use of synths here and there catch one by surprise. But they are applied to music that never changes mood, intensity, dynamics, tempo, nothing. The result is an album barely over half an hour in length that seems to stretch on into eternity, punctuated by all too brief moments of mild intrigue. I’m all for minimalism and monotony and I’m all for outrageously sloppy playing at times, especially within black metal, but this album fails to compensate for this with the usual caveats of atmosphere, audacity, character. Without that, I’m unsure why it exists.