Kill the bliss

At the risk of sounding infantile, I’ve come to hate summer. Aside from the needlessly long, skin damaging days, the clammy, sleepless nights, and the ambient good cheer of outdoor folk, life seems to reserve its more challenging scenarios for the summer months. I usually turn to the suffocating activity of death metal during a heatwave. Music that only aggravates the sensory overload of soaring temperatures somehow blunts its effects. But this summer has been uniquely trying. As a result, the noise diaries have spun off into unexpected directions. A recent – and largely failed – attempt to unpack escapism in metal has prompted me to explore some early Judas Priest, rediscovering the breadth of metallic tropes they anticipated in their formative efforts. Spinning some Erik Satie has reminded me that I’ve barely touched a piano in the last few years, something I intend to rectify after reacquainting myself with his opaque yet oddly accessible Gnossiennes. And finally, I’ve conceived a strong desire to experience pure, unadulterated music, a thirst that can apparently only be quenched by late 70s Tangerine Dream.

Erik Satie’s Gnossiennes are a notorious riddle of the post Romantic era. Satie himself was in many ways the paragon of anti-Wagnerian thought. His idiosyncratic, atempo harmonies, his careless minimalism, haunting surrealism, and playfully spiced distress. All this beckons even the novice pianist in, tempting them to give him a shot, only to find reams of complexity unfurling beneath the relatively sparse manuscripts. But it’s a complexity that restates, or rather develops, the importance of traditional, pre-classical era tonality in defiance of reckless Wagnerian chromaticism. Satie’s love of early church music and French baroque bleeds through into his free flowing, often barless notations.

His work is said to have heralded the arrival of minimalism, and has even been characterised as proto-ambient for its unresolved chord progressions, ambiguous melodic construction, and casual attitude to tempo and rhythm, demanding of the player gradations of interpretation in stark contrast to the heavy handed instruction cluttering the manuscripts of his contemporaries. Any pointers he does give were notoriously oblique, such as the requests to “arm yourself with clairvoyance”, to play “alone for an instant”, or to “open your head” littering his third Gnossienne.

The meaning of the term itself remains obscured. Satie essentially conceived of the Gnossienne as a new classical form. One that, setting aside any mystical connection to Gnosticism or Knossos, could ultimately be understood as an incomplete idea, a suggestion or nudge in a certain direction. A corrective to the strict rigours of the sonata, prelude, or nocturne, Gnossiennes as Satie understood them reassert a folkist informality, the performer is free to layer their character over his light touch notations. Whatever truth there is in this reading of the term, there is no denying the uncanny half life these pieces take on. A liminal spectre of proto thoughts, floating between sleep and wakefulness, hinting at something beyond their raw materials.

These rather mystical qualities are explicable, although no less esoteric for the fact. Firstly, there is Satie’s insistence on minimalism, which was something of a radical concept in the extravagant late 19th Century. Lacking the formal training of his contemporaries imbues his work with a sense of freedom and informality that is often mistakenly interpreted as simplicity. The pieces are sparse, transparent, knowable. This only serves to highlight his harmonic idiosyncrasy, with no lavish ornamentation or surplus activity to cloak the bizarre chord choices and drunken melodic flow they are left naked and alone on centre stage. Free of the completist landscaping of a Debussy, Ravel, or Mahler, these incidental expressions are the entire point of these rather brief pieces.

There are also the lilting rhythms, something performers are free to interpret as they wish given the lack of bars and time signatures (save for Gnossienne No. 5). That being said I tend to favour slower recitals, allowing the spaces between chords and the hesitant, decaying melodies to reinforce the at times unbearable tension couched within each piece. This is particularly true of Gnossienne No. 6 (to be played “with conviction and rigorous sadness”), whose bright, levitating ambiguity is akin to sobering up after a long session with no sleep, drunkenness still intruding on rationality’s dominion and the underlying sorrow brought on by the beckoning sobriety.

Lastly, outside of the proto-modernist qualities of these pieces, their emotional breadth and quiet rebuttal to classical forms makes them, from a player’s perspective, at once daunting and enticing. Technically easy to grapple with. Yet the lack of clear direction, the – especially with numbers 5 and 6 – lack of clear structure or repetition, and the open ended rhythms, all amount to an almost endless project of interpretation, reinterpretation, and revision. They invite the amateur pianist in, only to expand their understanding of the potential behind each substantively modest piece, forcing them to reckon with the limits of their ability as it collides with the sheer breadth of imagination Satie is wont to awaken in his audience.

Tangerine Dream’s discography is notoriously intimidating, their music pivotal to the entire cultural atmosphere of the 1970s and 80s. Starting at the beginning will get you informal art rock drones, proto ambient, and the unironic space worship of early 70s optimism. Starting from their third album through to the sixth gets you an imposing cathedral of swelling sonic energy, evoking the sheer intimidating size of the universe in stark contrast to the optimistic play of the earlier material. Heading into the 80s gets you a number of well loved soundtracks and playful synth music befitting of a decade now synonymous with play. But pausing on the late 1970s for a moment, from ‘Stratosphere’ in 1977 through to ‘Tangram’ in 1980, one will find Tangerine Dream perhaps at their most accessible and iconic. A bombastic and carefree bridge between 70s prog rock maximalism and the light touch miniaturism of 80s synth pop.

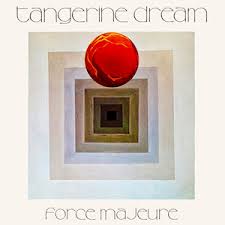

1978’s ‘Cyclone’ was an explicit attempt to reacquaint themselves with progressive rock music with the reintroduction of live drums, and a vocalist in the form of Steve Joliffe. Whilst I’ve come to appreciate this album for its poppy prog permutations and trademark interconnecting harmonies, it was not well loved at the time of its release. The follow up, 1979’s ‘Force Majeure’ saw them ditch Joliffe but retain the live drums and prominent guitar. And whilst these features frontload the album with more poppy prog sensibilities, the synths quickly take over in the latter half of the album, seeing Tangerine Dream reassert their meandering, bottomless sequenced harmonies pulsating by in mesmerizingly playful iterations.

Aficionados may prefer the dark mysticism of 1972’s ‘Zeit’ or the haunting abstractions of ‘Atem’, but there is something to be said for the abundance of pure music on offer in this era of Tangerine Dream. Each idea could form the backbone of a pop song, but as it mutates and develops over time it compounds into a rich soundscape of complementary themes and moods which, despite the unambiguous brightness, take the listener through a variety of emotional colours.

A perfect three act structure, the opening title piece is the most diverse emotionally and stylistically, taking the listener through poppy prog guitar work, elaborate synth orchestration, clunky piano, and the optimism of what, to the modern ear, sounds like retro futurism. ‘Cloudburst Flight’, the shortest and mellowest piece, functions like an instrumental ballad. Soaring guitar and synth lines set to driving drums, immersive yet knowable atmospheric currents, this is Tangerine Dream’s answer to radio friendly pop. The closing number, ‘Thru Metamorphic Rocks’, with its opening piano grooves and staccato string chords, also behaves like a pop song as it slowly gathers cathartic euphoria through the power balladeering guitar lines. But it eventually collapses into an imposing, hypnotic tour de force of elaborate synth layers as Tangerine Dream finally decide to unfurl their artificial side with pulsing, sequenced harmonies and driving rhythms forming a coda of proto acid house.

Plucked from the heart of their archetypical era, bridging the earlier experimental work with the accessible soundtracks that followed, ‘Force Majeure’, despite the abundance of raw material on display, offers something quite simple, a total and immersive musical experience. No moment is left undecorated, no melody unresolved, no sequence suspended in ambiguity. It is modern tonality at its most perfect and complete, yet contains within it the germinal of pop and dance music that would define the two decades following its release. Both the resolution of 70s album excess, and the starting gun of synth pop, modern ambient, and acid house.

What’s left to say about an album like ‘Stained Class’? The end of the classic trilogy, Priest at their most metal. Yes, aesthetically ‘Screaming for Vengeance’ or ‘Defenders of the Faith’ are closer to the platonic form of “metal”. But the compact nature of the tracks, their obvious verse/chorus flow, and reliance on anthemic breakers coats them with a pop rock sheen that no amount of frenetic neoclassicism can salvage. ‘Sad Wings of Destiny’, ‘Sin After Sin’, and ‘Stained Class’ by contrast embody metal as a philosophical project, despite being far less conscious of their metalness than 80s Priest. They simultaneously bind together the DNA of the genre whilst playing with its form through progressive rock excess, mutating heavy rock riff mores into their own sue generis language, and crafting ambitious narrative structures touching on both classical and contemporary forms.

‘Stained Class’ is perhaps the slickest and most realised of the three. The more direct NWOBHM tendencies beginning to creep in on tracks like ‘White Heat, Red Hot’ or ‘Savage’ are supplemented by the bright classicism of the lead guitar material on ‘Exciter’ or Halford’s wide ranging vocals decorating every track. What emerges is a work steeped in the lore of its time, the latent energy of punk, the ethereal mysticism of late 60s psychedelia, the carefree bombast of prog, and the boisterous arrogance of heavy rock. A repository of everything great about guitar music to that point. But emerging from above this amalgamation is a new, novel expression of fantasy and escapism, a kind of play run amok. The excess of riffs, the almost abrasive extravagance of the solos and lead melodies, and Les Binks’s insistence on forcing the drums up into the cadence of each riff, elaborating or redefining certain moments with insistent rhythmic emphasis. To this day, watching Judas Priest evolve the raw material available to them – and indeed building on the strong foundation established on the two preceding albums – in real time, elaborating it into something entirely novel remains dazzling.

That’s before we come to Halford’s rampant vocal work, seamlessly wandering between mid-range rock power and falsetto ejaculations peppered across the music at unexpected junctures. The lyrics range through themes that would become staples of metal in the decade to come, here found in germinal form. A liminal space between fantasy and reality, between desire and circumstance, before sinking into the final depressive capitulation that was ‘Beyond the Realms of Death’.

It’s this intersection of childish play, rampant darkness, a constant churn of activity, and power both at the substantive and implied level that makes this album so formative to the many branches of metal in the subsequent decade. It seems to flow out of the musicians effortlessly, as the pieces unfurl their identity with a freedom and confidence one may struggle to find in modern music.

A pleasant and stimulating read that made me dig out ye olde Tangerine Dream LPs for a revisit, thanks. Even if ”Zeit” might be their strongest artistic statement, the late-70s albums are more suitable for habitual listening. Always had a soft spot for ”Bent Cold Sidewalk”. They took a risk with that one and it paid off IMO.

JP

LikeLike