Why is metal such a stubbornly perennial passion? I’d venture that it’s not just the intensity and obsession it provokes, but just how deep and far the genre spread across the globe. If you ever feel the need to refresh your listening rotation, you can pretty much close your eyes and point to a place on the map, pick a decade since the 70s, and a subgenre, and you’ll find a rich body of material to unpack. It’s this very feature that also provokes endless and often bitter confrontations across its various scenes.

The story of death metal, for example, is annoyingly postmodern precisely because it lacks an agreed history despite the intense amateur scrutiny it has been subjected to over the years. There have certainly been many valiant efforts to conjure an official history. But the mechanism for establishing agreed facts remains elusive. For all the banality – and sleight of hand finger wagging at death metal’s latent conservatism – in Albert Mudrian’s recent interview with Antony Fantano, the broad brushstroke history they outline is one few would dispute. Death metal was a spontaneous outgrowth of metal and punk in the 80s, transacted via tape trading and handwritten letters, it negotiated its maturity through the corridors of Morrisound and Sunlight Studios, yet by the mid 90s it became exhausted, anaemic, and was largely abandoned by many of its most prominent practitioners. Since the late 2000s it has undergone a revival, and a tentative renaissance gradually bubbled up in the latter half of the 2010s.

The reason this narrative comes the closest to the “official” one is because it is backed up by what little data underground music has lying around. Namely record sales, number of tours, albums released, active labels, records of just how much money was sloshing about in the scene, and an assemblage of primary source material. But – and this is something I believe all parties should be able to agree on – the significance and indeed the story of art is not reducible to spreadsheets. It is increasingly the case that art gets multiple bites of the cherry to make an impact. An album’s resonance is no longer intrinsically tied to the specific context of its release.

Death metal’s fall from grace [sic] in the mid-90s was so dramatic and comprehensive that the output in the latter half of that decade skewed to polar extremes of blandness and avant-garde. The former is what has been remembered because this was largely produced at the hands of its more significant figures. The latter remains buried to time because it failed to gain enough momentum to influence the arc of the genre in the new century.

Plugging in a different geographical slant complicates the picture even further away from Mudrian’s “official” history, which chiefly recounts the American and partially Scandinavian picture. By the time David Vincent left Morbid Angel, citing disillusionment with the music and the diminishing returns of its extremity, Eastern Europe, for example, was opening up to the world. A host of young fans suddenly had access to what was essentially a moribund artform in the West by 1995. Death metal was maturing into its postmodern retirement.

But younger musicians from Eastern Europe were hardly viewing it on these terms. They were simply consuming music they loved, an arena that grew exponentially following the collapse of the Iron Curtain, and were suddenly afforded the opportunity to interject with their own interpretations. I had never given Romania much thought as a hotbed for death metal for example, the country being more closely associated with the popular pagan metal of Negura Bunget and Dordeduh in my mind. But over the last year or so the label Loud Rage Music has been reissuing relatively obscure albums from Romania’s past with a tempo that has prompted me to look again.

Taking the purely quantifiable view, these releases are insignificant curiosities. They made little impact at the time beyond their regional scene, and are only being dug up now thanks to the archaeological instincts of today’s internet metalheads veraciously mining the dustbin of history for lost classics.

This cynical view is one I’ve often adopted. But there are two glaring problems with it. One becomes apparent if we were to apply this logic to the likes of Demilich, Timeghoul, ‘The Red in the Sky is Ours’, or Winter’s ‘Into Darkness’. All remained relatively obscure at the time of their release but have, over the years, acquired a significant cult following and multiple reappraisals thanks to repeated pushes to place them back into the limelight. My collection would be all the poorer without these efforts. The second is the fact that Romania entered relatively late in the game, death metal’s founding documents were already established, and its innovators had either stagnated or moved on, leaving the genre for dead.

This left newer artists from Eastern Europe to pick apart the things they admired in the genre and begin to interject with their own opinions on its future direction. Essentially playing out in microcosm today’s choose-your-own-adventure approach by plugging a disconnected plethora of influences into the writing process.

Various bands seem to have picked up the threads of “stylised” death metal, shading in a preestablished format with a distinctive aesthetic character. This is most obvious in the rather literally named Gothic and their 1997 offering ‘Touch of Eternity’, which comes across as a kind of early Paradise Lost on Valium with all the clunkiness this implies. Or the straight edge blackened death metal of Dies Irae’s ‘Gargoyles’. Released in 1998 it offers a neat companion piece to Dawn’s ‘Slaughtersun’.

Ultimatum’s ‘Among Potential States’ released in 1996 could easily be read as the next chapter in the story of progressive death metal just as Pestilence, Atheist, Death, and Nocturnus successively departed from active service. The idiosyncratic mix of technical death metal, thrash, and shameless prog flamboyance works as the more intuitive sequel to ‘Erosion of Sanity’ when compared to the esoteric precipice Gorguts themselves jumped off by 1998. The mid-90s futurism of additional synth lines do date the work, as does explicit references to 80s material via Watchtower or DBC. But it represents the handbrake turn that was required of forward looking death metal at this time, one that sadly never gained the traction it deserved.

Routes to originality were not always evident or even desired however. Necroticism’s early hat in the ring ‘Exces Morbid’ offers little beyond standard death/thrash by the standards of the mid-90s. The Death worship of Taine’s ‘Cealalta Parte’ would have easily gone unnoticed if it was released in the wave of nostalgia DM of the 2010s. Korruption’s ‘Slaves of Darkness’ gets by on little more than enthusiasm despite the programmed drums dominating the flow and flavour of the music, immediately marking it out as unintentionally industrialist.

Artificial percussion is something they have in common with the exponentially more eccentric Deimos, whose two albums ‘Insane’ and ‘Death Squad’ were also reissued by Loud Rage Music. Originally released in 1997 and 2001 respectively, the “melodic death metal” tag on Metal Archives is certainly doing a lot of heavy lifting with these guys. Both releases are unapologetically disruptive entities. Provocative to the mores of genre and good taste. Arguably pulling on an even more basic riff traditional than ‘Heartwork’, with healthy doses of blunt thrash, groove metal, an Anglophone gothic sheen, and a boisterous, stadium rock posture. But Deimos glue these motley elements together in the most incongruous, abrasive, clumsy way imaginable that one is forced to conclude that offending the listener’s sensibilities was their intention all along. An unpleasant but decidedly thought provoking experience, like witnessing death metal enter its avant-garde phase in real time.

Outside of these more leftfield choices, late 90s Romanian death metal seemed to be more in keeping with general trends at the time. Namely exploring death metal’s integration into the still developing world of black metal, as with the aforementioned Dies Irae. Makrothumia, featuring future members of Negura Bunget and Dordeduh, offered a rich concoction of gothic and doom elements alongside a latent black metal puppetry on their sole outing ‘The Rit of Individuation’ in 1997. Avatar were exploring this from a different angle on the dark prog of ‘The Alchemist’ by the turn of the century, gunning for an explicitly contemporary sheen as a neat contrast to the arcane motions of Makrothumia.

Romanian death metal entered the conversation at a time when the genre was in a period of commercial decline. One can only speculate that this engendered a feeling of freedom within these musicians. The most respected artists in the genre had already dropped the ball spectacularly. What more was there to lose in toying with its forms? Deimos were undoubtably an example of this, as is the shamelessly melodramatic gothic doom of Abigail on their 1998 EP ‘Sonnets’, or the rampantly Cradle of Filth stylings of Hathor’s ‘Ancient’. Fans that value stylistic hygiene will find these gestures gauche and tacky, but in the spirit of exploration, embracing this continental eccentricity opens up a world replete with divergent pockets that fly in the face of good taste to the point of challenging why we are motivated to cultivate good taste in the first place. No matter where you turn something is happening.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the very-hard-to-Google ‘Beyond Tomorrow’, the sole album by Protest. Released in 1996, it’s a combination of slick death thrash and heavy metal bombast that – with no regard for future fans of ‘Absolute Elsewhere’ – effortlessly knits in vast sweeping gestures of synthwave, progressive flair, and a reckless theatrical abandon. As happened repeatedly in researching for this piece, I was forced to stop what I was doing and regard the music in full, “you can’t just do that and pretend it’s normal” is the thought that kept coming to mind.

And that’s the real – and undoubtedly safarist from a UK perspective – joy in undertaking these excursions into underappreciated locations and eras. Romania was one of many countries picking up the death metal baton dropped by Northern Europe, the UK, and North America by the mid-90s. What they encountered was a fully developed artform that failed to gracefully mature into its avant-garde or progressive iteration. Gorguts, Nile, and the bludgeoning techdeath carried forward by the likes of Deeds of Flesh being visible exceptions proving the rule.

The fact that these Romanian artists already had, by around 1995, a wealth of material to draw upon meant that many artists bypassed the germinal stage and entered their progressive era from day one. This impulse made any regional nuances look, to foreign ears, like eccentricities. The calcified mores of genre established in Florida and Sweden were suddenly split apart by a younger generation of Eastern Europeans who had little regard for how you feel about bolshy synth lines in that segment, or whether you can just insert a goth ballad part way through an industrial death/thrash/groove metal album, or blend Bon Jovi, Paradise Lost, and Slayer in the same bar.

A lot of this material lacks the refinement of a Morbid Angel, the technical ease of a Suffocation, the monomaniacal bombast of early Entombed. But that’s precisely the point. It exists to explode these tried and tested formulas. Pick apart the wreckage, salvage what it can and meld husks of previously unrelated material together with new bonding agents. The majority of this material made little impact at the time on the global stage. It is surprisingly hard to find even now (I had to resort to YouTube to track down a lot of it). But within this world, Romanian death metal between 1994 and 2000, one can discern the outlines of an alternative timeline where death metal embraced its internal contradictions, rejected the fate sealed for it by the music industry and declining record sales. And instead sought to go further and faster in the project of deconstructing the sensibilities of heavy metal formulas to the point of forcing us to question what good taste even means anymore.

More recent salvos into Romania reveal artists that may lack the wanton freedom of this earlier material – Rotheads, Vorus, Putred – but are nevertheless some of the more interesting acts currently working in death metal alongside their Chilean counterparts.

I’ve mixed feelings about this impulse to fire up the Google, pick a time and place, and begin shortlisting the dreaded “starter pack”. But I’m equally keen to continue corroborating my thesis that the late 1990s, far from being the nadir of death metal, is actually the lost third chapter in the genre’s evolution, forgotten now at our peril. As the genre jolts in fits and starts between nostalgia and impotent postmodernism, it’s worth remembering that it has been here before. And at the time, its response was far more assertive and adventurous despite the fact that these efforts were ultimately buried by time.

Listening list:

| Abigail | Sonnets | 1998 |

| Apostas | Suferind Nevinovat | 1997 |

| Avatar | The Alchemist | 2000 |

| Deimos | Insane | 1997 |

| Deimos | Death Squad | 2001 |

| Dies Irae | Gargolyes | 1998 |

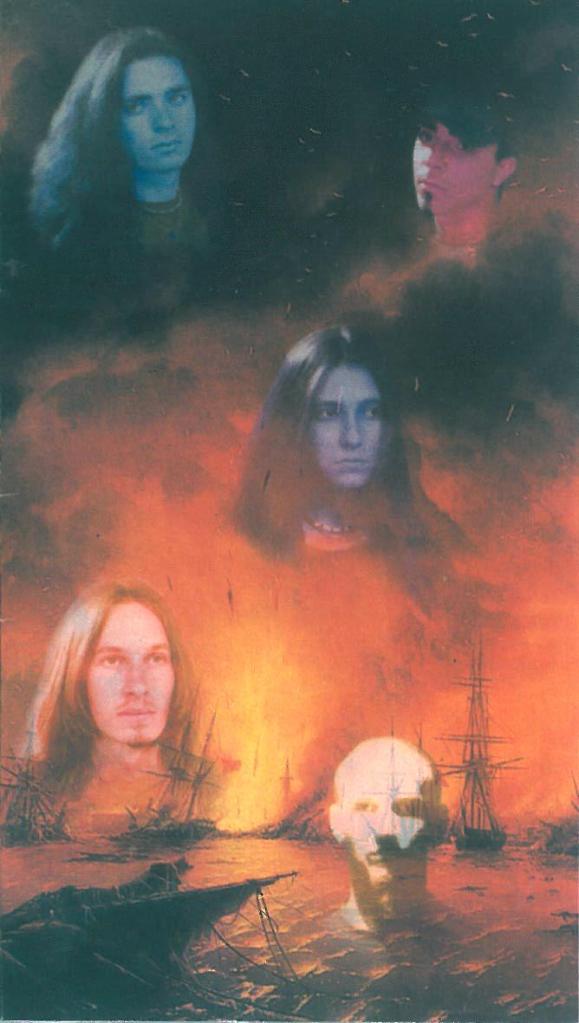

| Gothic | Touch of Eternity | 1997 |

| Grimegod | Dreamside of Me | 1997 |

| Hathor | Ancient | 2007 |

| Korruption | Slaves of Darkness | 1999 |

| Makrothumia | The Rit of Individuation | 1997 |

| Necroticism | Exces Morbid | 1994 |

| Protest | Beyond Tomorrow | 1998 |

| Rising Shadow | Tears of Sunset | 1996 |

| Taine | Cealalta Parte | 1999 |

| Ultimatum | Among Potential States | 1996 |

Not from Romania, but on topic of eastern european death metal, I highly recommend Nomenmortis from Slovakia

LikeLike

And Amorbital as well, also from Slovakia

LikeLike

Extremely interesting history here, great article. But I do want to offer a counterpoint:

Mortem released some re-recorded and new material on their magnum opus Decomposed By Posession in the year 2000, reinstating the original spirit and sound of desth metal. Many bands like Ascended (finland) and Dead Congregation followed very soon after; moreover, The Chasm continued unabated from the 90s into the early 2000s. The truth is that the story of death metals decline is only one, particularly pessimistic picture, which however persuasive it may seem, doesn’t do justice to the living tradition that stretched from the late eighties to today.

LikeLike