After the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, movements within metal tended to follow the same lifecycle of gestation, consolidation, and renaissance. After this creative and artistic peak genres would invariably meet a fork in the road. One path was to court major label attention, who would in turn dictate the terms of the metal’s intellectual suppression in readiness for mass consumption. The other path sees the “progressive” iterations of the genre take shape, often characterised by a new stage of intellectual maturity out of a once fresh faced and clunky arm of youth culture, now reforged as highbrow, avant-gardist art. The rise and fall of metal in its various forms from roughly 1980 to 2000 could be explained using this basic conceptual framework.

But if we are to document the Retromania complex within heavy meal during this time, a simple chronological history won’t suffice. We can shoehorn this framework into discussions of thrash, death metal, and black metal, all of which roughly followed the same lifecycle described above since their inception. We could contrive it into a discussion of glam metal, alt metal, and power metal, where it clearly does not fit, given that these were genre tags foisted onto artists who were grouped together by journalists and PR agents for the sake of marketability. A regrettable phenomenon which is often the driving force behind metal’s addiction to genre labels. But in doing this we would ultimately be covering well-trodden territory and offering to the table little more than a stylised Wikipedia article in the process.

The nostalgia complex can be identified in a plethora of moments throughout the 1980s. Early thrash was in part defined in opposition to the feminisation of heavy guitar music in the form of glam; reaching back to Motorhead and early hardcore punk to supplement NWOBHM melodicism could be seen as a logical response to this. But for a brief few years after this point the movement was lost in its own present, and some of thrash metal’s most remembered works were released. Then came the progressive phase, with the rise of Voivod, Watchtower, Coroner, and originators such as Metallica and Megadeth attempting to expand their sound into more fully realised compositions by the late 1980s. This saw the raw energy and immediacy of thrash diverted into ambitious and measured albums that were designed to be treated as such. Complex and lengthy works of layered composition offered to posterity in direct contrast to the raw grassroots anarchy of the movement at its inception.

Many genres of metal followed this rough cycle, with death metal reaching a similar pinnacle just a few years later. But in this dramatic climb to artistic maturity is found the seeds of many a genre’s destruction. The sheer energy and raw creativity will eventually burn itself out, with individuals unable to sustain the creative energy required for their near insatiable drive to annex the present. Commercial forces will then move in, who will try to sell the adoption of pop sensibilities as a sign of maturity, but in reality they end up forcing the music to regress back to its most basic components in readiness for a one-size-fits-all pop format.

This drama played out across the world of metal throughout the 1980s, with pockets of progression and regression cropping up at every level, from the deep underground all the way up to the perceived demands of fandom identified by major labels cashing in on the feast. But taken as read, these complexes were not specifically directed towards the past per se, but usually couched in the language of “back to basics”, “DIY”, or a raw need to find a unique voice in an increasingly crowded field. Nostalgia and the opposing impetus to “discover” a new sound were wrapped up in a complex network of other and sometimes contradictory motivations.

They were often a reaction to the immediate present, with artists looking back only a couple of years for a sense of context in order to discover their place and purpose within this music’s history. For example Darkthrone, in shunning the progressive direction of Death looked to Celtic Frost and early Sodom of five years earlier. What unified all the disparate threads of metal throughout the 80s was much the same as the original paradox at the heart of NWOBHM. A superficially regressive movement, lifting the aesthetic of biker gangs, old school rock ‘n’ roll, barbarism, and anti-modernist escapism; yet all this was a cover for what was in actuality a thoughtful, sophisticated, and at heart forward looking musical movement, demanding that the rock format that had captured Western youth culture so pervasively in the post war climate reach for something beyond a commercialised, radio friendly product.

This partly explains why we see this near constant churn of forward and backward motion in metal from the late 1970s onwards. A feature that came to define how collections of artists were understood by commentators. However, when metal was explicitly reaching for something in the past, it was usually antique rather than retro. Lifting inspiration from history, literature, 19th Century Romanticism, and sometimes even further back. Not so much a desire to return to a “simpler” time as it was a repurposing of old ideas into new frameworks and as yet undetermined directions. A sense of long term historical continuity rarely seen in Post War youth culture.

There were notable exceptions to this. Doom metal was perhaps the first metal genre to not only adopt a nostalgic style, but to actively celebrate this nostalgia. For modern listeners and other pondlife, pointing out that doom metal is the oldest metal genre has become a bizarre shibboleth. Never mind the fact that the statement is utterly false. As discussed in the essay on NWOBHM, Black Sabbath were barely a metal band, let alone members of a specific metal subgenre that only became solidified and self-conscious by the 1980s. The reason this banal feature of pub gossip has taken root is because of the collection of bands that reached popularity in the 1980s who swam against the tide of the speed and extremity arms race. Black Sabbath are no closer to modern doom metal than they are anything remotely NWOBHM sounding, despite being tangentially involved in the latter movement at the time. To say that doom metal is the oldest metal genre is a retrospective restructuring of the past, rewriting it in a way that touches on utter fiction. Nostalgia as propaganda.

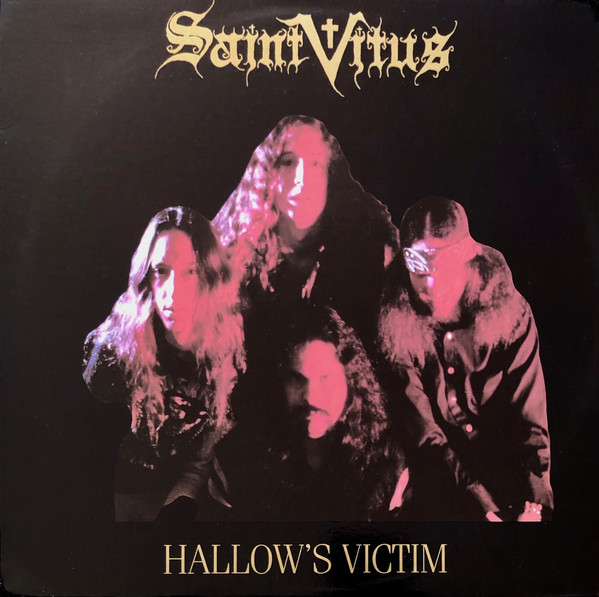

The unwitting flashpoint for this was probably Saint Vitus’s third album ‘Born too Late’ released in 1986, which became something of a rallying cry for metalheads nonplussed by ‘Reign in Blood’ released the same year, and the polar opposites that both albums represented. It wasn’t just the fact that one played fast and one played slow, it was everything about Saint Vitus’s aesthetic. They dressed like hippies, eschewing the spikes and leather of their peers, the cover art for albums like ‘Hallow’s Victim’ (1985) reached back to the 1970s, standing in defiance of the rich occult imagery and romanticist direction that the metal aesthetic was heading toward at the time, and the music itself was not only slow but also reached for the rich, mellow haze of 60s psychedelia, aiming to create a “vibe” as opposed to a frantic riff salad that was the defining feature of thrash metal. They, along with Pentagram, The Obsessed, and later the likes of Sleep and Acid King would anticipate the third coming of this genre in the mid to late 2000s.

The ‘Born too Late’ nostalgia and the first wave of what was to become known as stoner doom was unique for two reasons. One was the explicit yearning for a time now lost, that saw the present as an alien world, as demonstrated by the lyrics to the title track on ‘Born too Late’:

Every time I’m on the street

People laugh and point at me

They talk about my length of hair

And the out of date clothes I wear

They say I look like the living dead

They say I can’t have much in my head

They say my songs are much too slow

But they don’t know the things I know

I know I don’t belong

And there’s nothing I can do

I was born too late

And I’ll never be like you

The other key feature to note is the reach of this nostalgia. Saint Vitus and others were reaching back some fifteen years earlier, to an era before heavy metal was even an explicit genre let alone one engaged in an arms race of speed and extremity. In one sense this could easily be explained as Saint Vitus yearning for the music of their childhood. Or in Pentagram’s case having formed as early as 1970, they were simply reaffirming the music of their favoured era as superior to the direction guitar music had taken in a post NWOBHM world. But for the bands that followed on from this in the early 1990s, from Sleep to Cathedral to Electric Wizard, Retromania’s seeds were being planted in the pre-internet world, well before new technologies would grant younger fans unlimited access to all of music history.

In taking a birds-eye view of the 1980s however, it’s fair to say it was THE metal decade. Innovations in musical techniques were developed on every instrument in metal’s toolkit, along with the addition of plenty of new tools in the ever-expanding world of music technology, new scenes sprouting up all over the world, and some of the most ambitious guitar music put to record being released; all led to journalists and commentators scrabbling for the vocabulary to fit the moment. Many of the genre labels that had their origins in the 1980s only gained traction after the fact, having no meaning for the players on the ground at the time. Despite pockets of regression and an inbuilt fear of history’s onward march common to all humanity, the decade saw no end of spontaneous and joyful creativity, unabashed by time and place, with no concern for historical orientation. By the time the 1990s rolled around, many of these trends would continue, whilst others would wilt and die. And in their place an ever more complex and thoroughly surreal picture would take shape. A perfect storm created by the meeting of money, futurism, the ravages of aging, and millennial unease, all would give rise to what we now understand as perhaps metal’s weirdest decade.

Metal’s Retromania Part II: the great explosion

Metal’s Retromania Part IV: the Icarus factor

Metal’s retromania Part V: whither is fled the visionary gleam?